by Judith Altruda | Jan 4, 2025 | Portrait of Gene

Shoalwater Bay Tribe field trip to the Washington State History Museum, November 2024. L-R: Keven Shipman, Winona Mail Weber, Davin Culp.

More than 30 years after his death, Eugene Landry, artist, is gaining long overdue recognition. The response to his ongoing exhibits at the Governor’s Mansion and the State History Museum have been overwhelmingly positive—and personal. Many who previously had never heard of Eugene Landry, leave the exhibitions referring to him as “Gene.”

For those who knew Gene in his lifetime, seeing his art on the museum walls is especially gratifying. In November 2024, the Shoalwater Bay Tribe’s Education Department sponsored a field trip to the State History Museum in Tacoma. The stories flowed as Gene’s former portrait models toured the exhibition and recalled what life was like on the reservation in Gene’s time.

What is Native Art? Eugene Landry and the Creative Spirit will be on display through March 30 2025.

PLEASE NOTE:

From January 2 through January 12, 2025, the museum will offer discounted admission with access to special exhibitions on the fifth floor only. Exhibitions on view include “The Mountain Was Out,” “MAKERS ON THE TIDE: The Willits Brothers and Their Handmade Canoes,” “Collections Selections: A Parachute from the D.B. Cooper Investigation,” and “What is Native Art? Eugene Landry and the Creative Spirit.”

The entire museum will be closed from January 13 through February 17, 2025, to install a new permanent exhibition, “This Is Native Land.” The museum will reopen on February 18, 2025, with contained construction continuing in the Great Hall of Washington History. “This is Native Land” is set to open in the summer of 2025.

Sharing here photo highlights from the Shoalwater Bay November 2024 field trip:

Gabriel Landry with his portrait by Gene, 1966.

Tribal members loaned items of modern Shoalwater Bay history for the exhibit, such as 1970s jeans jacket embroidered with Tribal insignia. Photo by Keven Shipman.

Monty Baker, standing next to portrait of his uncle (and Gene’s cousin) Kenneth “Poggie” Baker.

Winona Mail Weber, gesturing to portrait of Nina Bumgarner, her maternal grandmother, daughter of Chief George Allen Charley.

by Judith Altruda | Nov 3, 2024 | Portrait of Gene

Landry’s exhibit at the Washington State History Museum in Tacoma will be on view until March 30 2025.

by Judith Altruda | Sep 23, 2024 | Portrait of Gene

State Capitol Dome (adjacent to the Governor’s mansion) Olympia WA. Photo by Marcy Merrill 2024

A few years ago, while seeking venues to host a traveling exhibit of Eugene Landry’s art, I contacted the director of a PNW museum whose mission is to “reassess the hierarchy of Northwest art history by advancing the work of women, minority, and other artists who historically [1860-1970] made substantial contributions to the region’s cultural identity.” It certainly seemed like Gene might qualify as one of those “hitherto neglected artists” the museum sought to recognize. I sent an email to the museum’s director with a link to this website and got a quick reply:

“…Unfortunately, I don’t think [ X museum] would be able to consider his work for an exhibition…portraiture of unknown people would not go over well with the general public.”

What a way to underestimate and devalue the general public! It made me ponder how women, minority and other artists were able to make “substantial contributions to the region’s cultural identity,” if they were “hitherto neglected?”

The director’s dismissal seemed counter to the museum’s mission statement, yet it was typical of the marginalization Gene Landry faced in his lifetime. As a Native American and a paraplegic, he faced enormous barriers as he pursued his artistic goal—of visibility. None of these obstacles, be it stairs blocking wheelchair access to art supply stores or curatorial gatekeepers stopped Gene from creating. Rejection did not deter him. For Gene, overcoming obstacles was a way of life.

In about 1962, after losing the use of his dominant hand through the negligence of attendants at an Indian Health Service facility, Gene returned to art school and started all over again, learning to draw and paint with his left hand. In the mid-60s he could often be found at Pioneer Square and other (then) downtrodden Seattle locations, drawing the “unknown” people of the street. He painted portraits of his tribal relations, friends, and wife Sharon. In addition to the portraits, Gene painted still lifes and landscapes reflecting the world around him. He had solo shows in the Puget Sound region and won awards at juried NW festivals. Against great odds, by age 30, Gene had become a practicing, professional artist. However, after his death in 1988, at age 50, Gene’s art had largely been forgotten by the world beyond his reservation.

Thirty years later, I uncovered a trove of his art in an attic. Despite decades of neglect, these paintings were survivors. Even in the darkness, through a film of dirt and mold, the faces of these “unknown people’ stirred me to action. Partnering with the Shoalwater Bay Tribe in 2019, we staged an exhibit of Eugene Landry’s art that opened (after two years of pandemic rescheduling) in 2021. Two years later, Gene’s art crossed the Columbia River to find acclaim in Astoria at the AVA, a non-profit gallery. Which opened the doors to two more exhibits, both opening this month in Washington State; one at the Governor’s Mansion in Olympia, and an extensive display at the Washington State History Museum in Tacoma. Hopefully the general public’s’ interest and appreciation of Eugene Landry will continue to grow, thanks to this recognition. We would like to see his exhibit eventually travel into other states—and maybe even the “other Washington.”

In the words of Margaret Cho, “The power of visibility can never be underestimated.”

Gene’s models for this collection, “Faces of Washington State” lived in Seattle, where he made his home between 1960-1968.

RECEPTION

On September 17th a grand reception hosted by the Governor’s Mansion Foundation, celebrated the work of four PNW artists/writers. Sharing a few photo highlights below. Gene’s work will be displayed in the public tour until 2026.

Program cover for the reception

Gene’s Shoalwater Bay and Quinault family members in attendance

Speeches and storytelling in the adjoining ballroom

Me with Washington State’s First Lady Trudi Inslee (L) When I thanked her for having us in her home, Trudi said, ‘Oh no, this is YOUR house.’

At the entrance to the Governor’s Mansion, L-R Leatta Anderson, Judith Altruda, Frank Shipman, Lynn Clark, Davin Culp. Photo by Marcy Merrill

by Judith Altruda | Dec 29, 2023 | Portrait of Gene

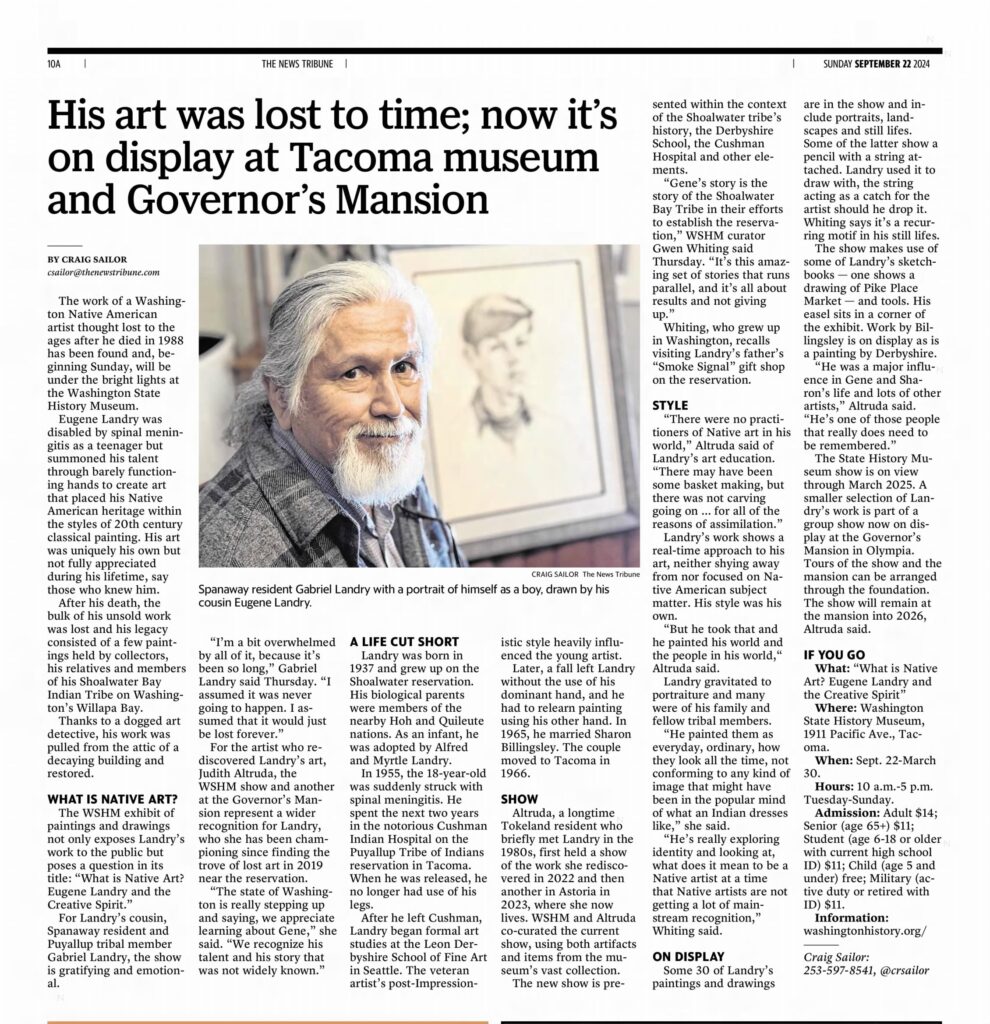

Spanaway resident Gabriel Landry with a portrait of himself as a boy, drawn by his cousin Eugene Landry. Craig Sailor The News Tribune

On the opening day of Gene’s exhibit in Astoria, journalist Craig Sailor happened into the gallery by chance. He had never heard of Eugene Landry or his art, but viewing the show, Sailor, a reporter for the Tacoma News Tribune, knew he had encountered a powerful story. Although “fascinated by all the elements,” his focus is on Landry’s years in Tacoma: the art he made while living there, his years at the Cushman Indian Hospital, and how “Landry’s story was another in a long, tragic history of the hospital and its predecessors.”

Read the full story (including a short video interview with Gene’s cousin Gabriel Landry) here